-a time machine installation –

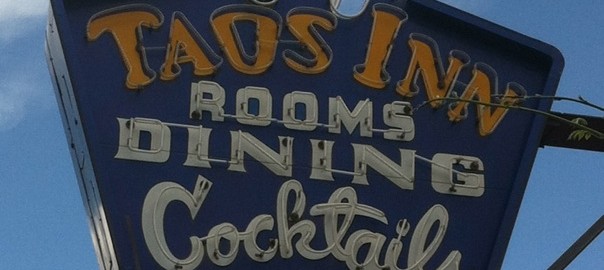

Machine, you have clay on your track pad and between your keys, and we have run up to the descriptor-gnashing, very good, verrry good, perhaps, the best, writing hole in all our times – the small, sunken fire pit adobe bench, with long ample cushion, in the lobby of the Hemingway-worthy Taos Inn. Timbers! Light! I would be most polite if I turned your one glass eye to the room. This is a handmade building with soft, curving white adobe planes, double-story to the square ceiling of subtly-pitched timbers like great-grandfather Lincoln logs.

How can this room be? Arches and lines, squares and meandering curves, a balcony lopes over the mysteriously interior-annexed triangular bar. Is the other side of the cave bar a wedge-shaped janitor’s cave? It’s summer. There is, thank all deities, no air conditioning. Two busy brass ceiling fans whir close to the vaulted timber ceiling.

The lobby is a puzzle, tough and easy, with four skylights and an octagonal cupola of light that make a prominent, secret message symbol of New Mexico. In the corner of the lobby, our fire pit is a jigsaw piece, publically secluded, with every amenity: sturdy table, ability to sit cross-legged without appearing homeless, the alpha seat in the room, a waitress for me, and an electrical outlet for you. Navajo rugs drape over the strange, white picket balcony. Last night there was a band in the lobby, an angel in a stiff blue shirtdress and innocently crooked lipstick, who sang 1940’s western songs like she wrote them herself yesterday morning.

I wanted to stay by her, but , a soul- friend was readying to play bass in a local band in a nearby bar. And I was going to get to help.

I am exalted running after dark, at high altitude, through narrow adobe hallways with heavy black canvas bags and musicians, late for load in. I thought to myself, this might be how it all ends, full-bore running with heavy equipment bags through the narrow, populated, winding adobe cave-ways that connect the businesses of the Taos square along the back wall, the not-for-show outer edge, that in a city would be an alley, through corridors smaller than they make anymore, pound pound pound my boots hammering at the alternating floor materials that each business has chosen for its section, wood, carpet, suspended hollow plywood, broken cement, tile with drain, inside outside, ‘scuse me pardon me, what is in these rectangular bags? These guys run fast like they are not kidding, they are late, they are hauling it way faster than social niceties travel. We are bumping into walls and closing propped doors as we stampede, ducking and leaping, everyone has a hat and a nickname, and I feel like I have joined the circus for real. These musicians have never played together before, and they are late.

The gig came to be through an agreement among buddies, locals in the egalitarian Taos music community that includes but is not limited to professional full-time performing musicians. One of them is my everlastingly-talented friend who was set to play bass this summer desert night alongside an enormous, long-haired, smokin’ Alabama-style guitarist with a single letter for a name; a sassy, petite Gladys Knight singer with a skating, Aretha vibrato and a name and face that defy racial classification in favor of depicting unclassified, formal Beauty; a tight, crackling Stewart Copeland-y drummer, whose girlfriend, I discovered from the audience side of the stage, puts a new, sparkly silver pin on the map of crazy chicks; and finally an enthusiastic electric guitarist who clearly still needs lessons, and who helped the entire experience, made it local, made it even more real, when he eagerly cooled the joint with an attempted Mark Knopfler riff. The rest of the band quickly swooped us all, him included, back to the heavens with a properly executed Cinnamon Girl. I danced like I ought to leave town this morning.

And yet here I sit, three steps down from the main floor, in the half moon arc of the fireplace pit in the lobby of the Taos Inn. It is the perfect hiding place for us, Machine. I can’t see what items, likely historic to the Inn, are featured in the shallow adobe inset display window. They are obscured by the reflection from the bright patio across the lobby, the leaves and red umbrella half-real again in the glass, warbling, and commingled with a word, another dimension, painted painstakingly in an arc, unconcerned with what year it is, in gold apothecary letters

KIMOSABE